For Gloucestershire-based arable farmer and agricultural contractor, Phil Odam, using crop canopy sensors to detect weeds in stale seedbeds and vary sowing rates accordingly has helped to reduce Blackgrass populations on infected land. And by using the sensors to detect subtle soil changes, he is also varying drilling rates according to soil type.

Philip Odam Agricultural Services provides a range of cereal and grassland contracting services from its base at Butlers Court near Cheltenham. For the company’s owner, Phil Odam, who also farms 600 acres of arable land, the use of crop canopy sensors is just one way in which he is focusing on improving arable yields and crop consistency.

“Despite the potential for modern wheat cultivars to produce huge harvests, UK yields have plateaued,” Phil explains. “I’ve always been keen to understand how to unlock better yields, not only for my own crops, but to add value to my contracting customers. We’ve therefore been yield mapping and using variable rate fertiliser applications for the past six years to improve combine output by producing uniform, easier to harvest crops.

For the 2016/17 season Phil replaced his original N-Sensor with a Topcon CropSpec system as he wanted to monitor Blackgrass populations and to vary seeding rates accordingly. “We’ve found that the CropSpec sensors can be used for much more than simply assessing a crop’s nutrient requirements,” he explains. “In addition, they can also be used to identify areas of high Blackgrass infestation and to automatically compensate by increasing the seeding rate.”

Instead of ploughing to bury Blackgrass seeds, Phil prefers to “keep the enemy in site” and as such delays drilling to allow the seed bed to produce two to three flushes of weeds, the last of which is sprayed off with glyphosate 24 hours prior to drilling. “We then use the canopy sensors on the drill tractor to detect the still-green seedlings, with heavily contaminated areas receiving more seed and vice versa.”

For winter wheat, Phil aims to achieve 350 plants/m2. “We vary the actual drilling rate between 150 and 250 kg/ha, using the higher rate to out-compete any subsequent Blackgrass flushes.

“In a couple of seasons, we’ve reduced our Blackgrass return rate from more than 300 plants/m2to less than 30, with several fields that were heavily contaminated now as low as 4 or 5 plants/m2. A lot of that success is a direct result of delaying drilling and crop rotation, but as anyone with a Blackgrass problem knows, it’s a long-term strategy and controlling the last few plants which makes the biggest difference. Using the wheat crop to out-compete Blackgrass means we’re now in a position where we can maintain a sustainable level of control with the chemistry and machinery currently available.”

Phil has also discovered, somewhat by chance, that the canopy sensors can be used to detect subtledifferences in soil type. “I noticed whilst drilling fields with no volunteers or Blackgrass that the sensors where still picking up changes in terms of seedbed reflectance,” he explains. “With no biomass to reflect off, I didn’t know what the sensors were seeing, but they were automatically upping the seeding rate on more open seed beds, and reducing it on the better, finer tilth land.”

By studying the data generated by the sensors, and comparing it with his own knowledge of soil variations across the field, Phil recognised that the sensors were returning a higher reflectance reading for soils with a higher clay content, and a lower reading for soils with a greater sand content. “We subsequently used that data to increase the seed rate for heavier land, and to reduce it on more favourable soils,” he explains.

“In effect, the sensors were making the same adjustments to the seeding rate that I had been doing manually for the past few years. But unlike manual adjustments, the canopy sensors work automatically, which means if the phone rings while I’m drilling, it doesn’t matter if I get distracted and forget to reset the seed rate.

“Essentially, we’re using live scanning to assess soil conditions in real-time as opposed to relying on satellite imagery, conductivity maps or prescription soil maps which, as well as being out-of-date by the time the drill is working, are also costly and time consuming to produce which doesn’t suit our own needs or those of our customers.

“Only time will tell if changing our drilling rate in this way will significantly increase yields, but in the short-term we’re getting on top of Blackgrass and have made good progress in terms of eliminating the lodging threat and ensuring crops are grown evenly and consistently irrespective of soil variations.

“We’re also hoping to use the CropSpec sensors to make variable rate growth regulator applications this season and have already started thinking about how they could be used to make variable rate fungicide and organic manure applications.”

- Normally mounted on the cab for spraying and fertilising, the small size and flexible mounting options of the CropTec sensors allow them to be positioned in front of the tractor for drilling, thereby giving a high definition view of the soil being drilled.

- The seed rate is increased where Blackgrass is detected. Heavier soils also received a higher seed rate.

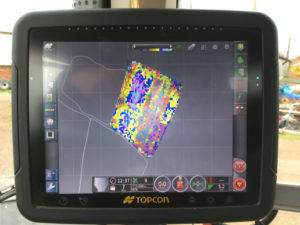

- The crop sensors clearly illustrate differences in soil type across single fields: the grey area to the right is dominated by clay, while the left of the field is of a lighter soil type

- Armed with the necessary data, the Topcon X30 controller automatically varies the seeding rate according to soil type or density of Blackgrass plants.

- Fertiliser is applied at a variable rate according to the crop’s real-time nutrient requirements.